Migrating a primary key column from INT data type to BIGINT data type in a relational DB2 Database

Context

This article intends to present all technical challenges in solving a very challenging problem: how to migrate a primary key column from INT data type to BIGINT data type in a very large database when the number of KEYS is running out of sequences.

The main intention is to provide you with a way to follow (or inspire) if you are facing a similar challenge. Besides that, there isn’t much content out there in this area to help you minimize risks, predict possible problems, and reduce the total time spent on such an endeavor.

The work presented in this article was taken by a fully competent team composed of 7 engineers, who worked hard to fix the problem on time. Business and domain details are not presented here. Therefore we refer to generic structures, names, and definitions throughout the article.

Problem

A key exhaustion problem arises when the following conditions are met:

- There’s a table created with a numeric primary key column set to be of a DATATYPE limited on a $MAX$ number (e.g.: INT).

- For every record insertion you increment the key by one (e.g.: $KEY_{next} = KEY_{current} + 1$)

- In the event of inserting a record with $KEY_{next} = MAX+1$, then the $MAX$ limit is overflowed and the database starts throwing errors for all following insert commands.

In this particular scenario, the application was composed of a front-end, a back-end, and a database containing a few hundred tables used to store and process some information. The system operated in two critical contexts: 1) to communicate with other applications and provide processual data, and 2) to provide data for reports and analytics generation.

The database contained a huge $main$ table responsible for storing new records for every new business transaction. This table met all the conditions above except condition 3, by the time we found out that we would run out of keys, we had 12 months ahead to fix the problem.

The keys exhaustion began when the system started to be more extensively used. The number of records being inserted daily peeked at around a few hundred thousand on the main table. The $main$ table was created using a primary key set as INT data type, and in IBM DB2, the maximum numerical value supported for an INT is exactly 2147483647, which means that when we inserted the record with a key value equals 2147483648 the application would stop accepting new business transactions.

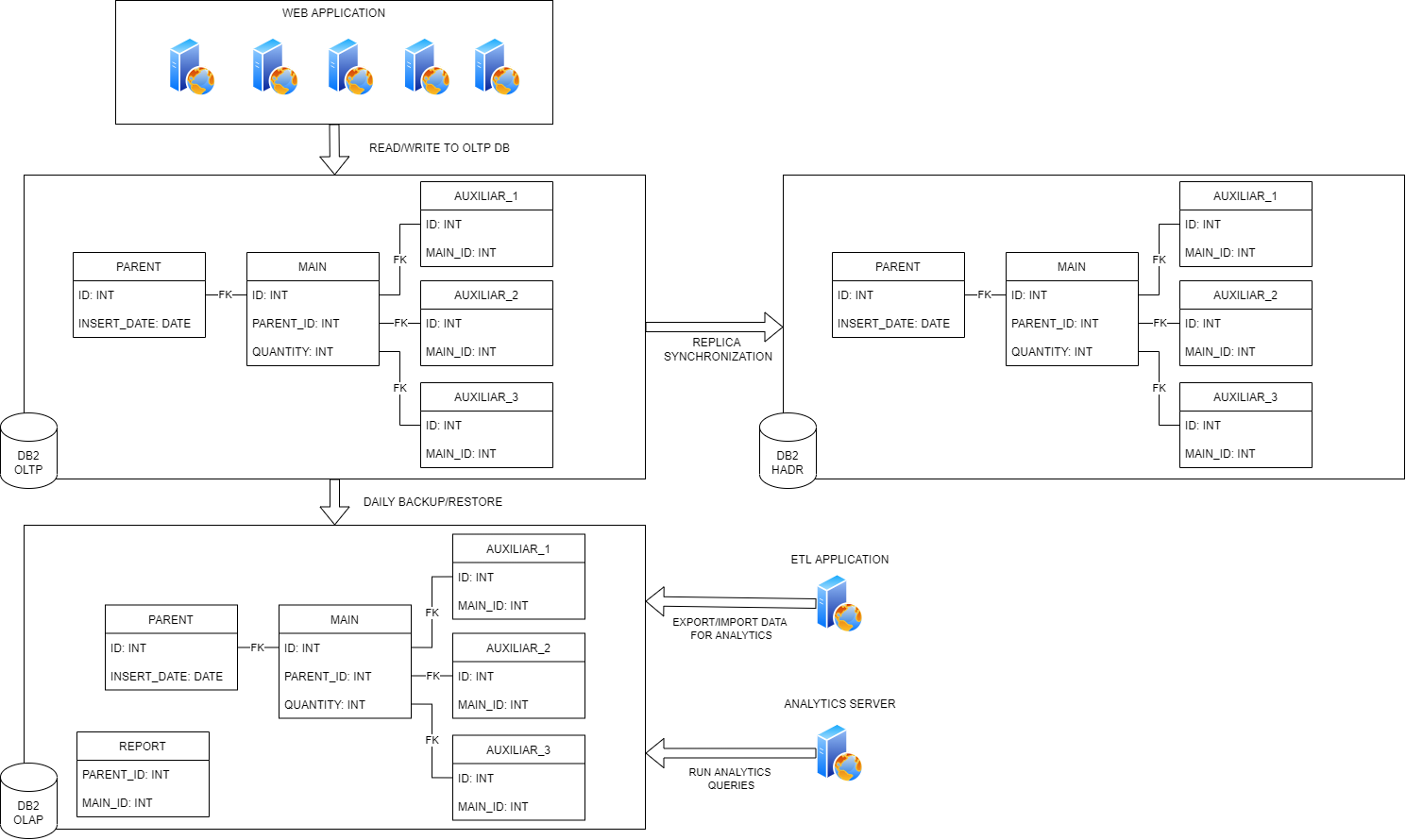

The following diagram depicts the general system architecture. The system was composed of various Web Application nodes processing business transactions (reading and writing to the OLTP DB). There was also a reporting/analytical database used for ETL transformation and report generation. And finally, there was an online synchronized high-availability disaster recovery replica to the main table for fault tolerance.

Diagram 1: Application Architecture Diagram

Constraints

The current application technology (DB2 and Java Web), and also the business context, imposed some constraints on our freedom to design the solution. The list below presents the main constraints on the project:

- We couldn’t afford more than 1 hour per week of downtime for maintenance due to business requirements.

- The $main$ table had a very large watermark disk space usage, which meant we couldn’t change the table schema anyhow as it would require a re-org operation. Re-orgs are quite expensive depending on the table size, in our case, we forecasted various hours for finishing one. It was not an option.

- All operations made in the OLTP database had to be logged operations so that they could be replicated to the HADR DB replica. This was necessary to avoid the risk of not having a fully synced failover database.

- The current reporting DB strategy was based on a snapshot copy and restore strategy of the daily OLTP DB to the OLAP DB. This operation used to take around 6 to 10 hours to finish so the ETL and analytical apps could start working by noon. We couldn’t refactor this strategy as it would compete with the 12 months’ time to run out of keys.

- We couldn’t delete records from the main table to reduce its size as some policies and regulations required all the data to be present in the database.

Impact Analysis

Because the target of the change was a column running out of keys, the first step was to start the impact analysis and check what would be the blast radius of allowing the storage of BIGINT values (BIGINT > MAX INT in the current context). Therefore, based on the endangered key (e.g.: table MAIN.ID from the diagram above), we started to look for every place where the particular ID value was used.

We started by looking at all tables affected in the same OLTP database. From the image above:

- AUXILIAR_1.MAIN_ID

- AUXILIAR_2.MAIN_ID

- AUXILIAR_3.MAIN_ID

All database objects:

- Procedures

- Triggers

- Views

- Materialized Query Tables

All the tables affect other databases (OLAP database):

- REPORT.MAIN_ID

All the external contracts shared with other systems through REST or SOAP carried the endangered key:

- JSON requests/responses

- XSD XML requests/responses

All usages in the source code that referenced the endangered key (including the main and auxiliary table columns):

- ORM mapping

- SQL queries

- int and Integer variables in Java classes and JSP files

- all JavaScript variables presented on the front-end

All usages in ETL jobs (OLAP DB):

- Linux jobs exporting comma and space delimited reports for analytics

- Data analytics applications querying the database for reports

Ripple Effect

The most challenging aspect of the impact analysis was calculating the ripple effect. For different types of objects, we had to use different strategies to figure out how the information was propagated. Every time we found a new impacted place (system, variable, column, script, or field), we had to start a new ripple effect analysis from that place to find other places referencing the just discovered affected object. This process was required to make sure the information would flow normally when a value larger number greater than INT would pass through. For example, the diagram below shows how a database column could span multiple levels of propagation in the Java source code. In this example, you can see that every time we find a new affected variable, we have to trace its usage and create a new ripple effect from that point onwards:

MAIN.ID (database column)

|-- ref in --> var id = rs.getInt("ID") (class A line 10, traces "id")

|-- ref in --> int getId() { return id; } (class A line 50, traces "getId")

| |-- ref in --> if(a.getId() > x) { (class B line 24, traces "x")

| | |-- ...

| |-- ref in --> Integer t = a.getId(); (class C line 40, traces "t")

| | |-- ...

|-- ref in --> void setId(int i) { this.id = i; } (class A line 60, traces "setId")

|-- ref in --> a.setId(t); (Java class D, line 50, traces "t")

|-- ref in --> int t = b.getMainId(); (class D line 40, traces "getMainId")

|-- ...

When we finished mapping the first round of affected code variables, scripts, systems, databases, reports, CSV files, front-end views, procedures, views, triggers, SQL, etc… Then we started to think about the solution. Worth noting that the impact analysis was not a one-time job, we had to repeat it every time something new was discovered. This process happened uncountable times until we were done. Even after releasing the first deployments to fix the problem we had to recur to the impact analysis sometimes.

Solution

During the solution phase, we considered many possible alternatives. Each solution had a set of benefits and drawbacks, so we scrutinized them as must as possible to make a conscious decision. The following sub-sections present the alternatives with a brief description of how they would work and the advantages and drawbacks of each one.

Worth noticing that the next two solutions (Re-using keys and Negative Keys) didn’t require re-writing any source code to couple with long values, as the table’s key values, would still be less than Integer.MAX_INT.

Re-using keys

The idea of this solution was to look at the records on the $main$ table to find a sufficiently large range of free keys where we could set the sequence generator to start from the beginning of the range. For a better definition assume there are two key values $k_{l}$ and $k_{u}$, given $k_{l} < k_{u}$, where for every key $k$ existent in the $main$ table the condition $k \notin [k_{l}, k_{l} + 1, k_{l} + 2, … , k_{u}]$ holds. Also define $R = k_{u} - k_{l}$ as the number of keys to be reused, the idea was to find two keys $k_{l}$ and $k_{u}$ where we could maximize the value of $R$.

The main benefit of this solution was the simplicity of the idea. Given we could find a sufficiently large value for $R$, then it would only require setting the $main$ table sequence generator value to start off from $k_{l} + 1$.

The main drawbacks of this solution were two. Firstly how big should $R$ be to prevent running out of keys again in the long term? When we detected we were running out of keys in 12 months, the table had barely overpassed the 1.5 billion keys, which meant that by keeping the same rate of inserts the application was consuming 30% of the max INT value every 12 months. Of course, this solution was not sustainable in the long term as the business didn’t show any signs of slowing down. Secondly, there was a risk of reusing deleted keys from the database, but for some reason, kept persisted in other systems. In this situation, if a particular deleted key would be assigned again to a new record, the application would corrupt other systems. The second drawback was the principal factor to put off from the table this solution.

Negative keys

This solution is similar to the re-using keys one. The difference is that we would reset the sequence generator for the key column in the $main$ table to the minimum negative INT value supported.

As per the previous solution, the implementation would be easy. It would only require resetting the sequence to the minimum negative int. However, this solution was also not sustainable in the long term. We expected to run out of keys again in 3 to 4 years. Besides that, we were afraid of unpredictable behaviors by spreading negative keys around.

The main drive not to decide on this solution was given by the team’s confidence. We didn’t believe it was the right thing to do, and we couldn’t predict how other systems would behave with this information.

Alter table command

The alter table command solution is as simple as it sounds. The idea was to issue the following DDL commands to the DB2 database and hope for the best.

ALTER TABLE MAIN ALTER COLUMN ID SET DATA TYPE BIGINT;

REORG TABLE MAIN;

ALTER TABLE AUXILIAR_1 ALTER COLUMN MAIN_ID SET DATA TYPE BIGINT;

REORG TABLE AUXILIAR_1;

ALTER TABLE AUXILIAR_2 ALTER COLUMN MAIN_ID SET DATA TYPE BIGINT;

REORG TABLE AUXILIAR_2;

ALTER TABLE AUXILIAR_3 ALTER COLUMN MAIN_ID SET DATA TYPE BIGINT;

REORG TABLE AUXILIAR_3;

ALTER TABLE REPORT ALTER COLUMN MAIN_ID SET DATA TYPE BIGINT;

REORG TABLE REPORT;

This solution had the main benefit of requiring only to issue a few DDL commands. In terms of implementation complexity, it was simple. The main drawback was the time it would take to run the REORG operation at the database’s $main$ table. The $main$ table had around 2TB of data, so we estimated a couple of hours to complete the operation that we couldn’t afford. However, for small tables that could be a viable option.

Another implication of this solution was the necessity to refactor all places referencing the $main.id$ column to handle long values. However, as the two previous crossed-off solutions were the only ones that didn’t require this re-factoring, the team had made up its mind that refactoring the source code wasn’t a major drawback.

Admin Move Table

The admin move table solution is based on an IBM feature in DB2 that allows you to migrate all data from one table to another table (with a new schema) by issuing a single command that will do everything at once. This command works as follows:

- You specify the origin table

- You specify the target table (perhaps with a new schema definition)

- You start the move admin table command

- DB2 creates a bunch of auxiliary tables and starts migrating all the data. The origin table is not blocked from continuing to be used.

- Once all the data was migrated, the command swaps the original and the target tables.

The main advantage of this solution was its implementation simplicity, the complicated part is understanding all command phases and side-effects before running it. Nonetheless, this solution had two main drawbacks in our case that blocked it off from the $main$ table.

- It would fully duplicate the $main$ table, in other words, instead of having a single table with 2TB the DB would have to accommodate two tables with 4TB. Therefore, this solution would impact the backup/restore reporting database process. By the time the project started, all daily reports were already delayed until noon because it was taking 6-10 hours to run the backup/restore process. By taking this approach we wouldn’t be able to enable the reporting DB on time.

- However, the show blocker was the non-logged operations of the admin move table command. It means that this command would not be replicated in the HADR database. If we followed this approach we’d take the risk of not having a fault-tolerant replica to failover in case of outages. We couldn’t afford this risk.

Create a new column

The solution “create a new column” had two flavors in our evaluation. We could create a NEW_ID column defined as BIGINT, synchronize all keys from the old ID column to the NEW_ID, and then change the source code to the NEW_ID column. Or another alternative would be to create a new PREFIX column that would work as a prefix for the current ID column and rotate the main ID every time we increase the PREFIX by one.

The NEW_KEY column had some benefits, it was not that complex to implement on the database side but it would require extensive code refactoring on the application and reporting side.

By the time of the project, the application didn’t use any kind of ORM framework and there were hundreds of native SQL queries to re-write. Besides that, we also had to change all the code to couple with the long data type. So the refactoring was a show blocker for this solution.

The PREFIX column was even more complicated, on the database side it would require changing the primary key index of the table to be composed of the prefix and key columns. Otherwise, we would get a duplicated key exception when rotating the key for the first time. Besides that, we would need to refactor all SQL statements to see the KEY property as the composition of concat(PREFIX, KEY). For this one, we didn’t spend much time as we felt it was quite obvious a bad idea.

Duplicate table and migrate active data

This idea has roots in the admin move table solution. The difference is that we wouldn’t migrate all the data in one shot, we would start with all “active” records to keep the operation going, and trickle-feed the remaining data after the BIGINT key table was in place.

Depending on what “active” means, this solution could be the most viable option. With it, we could work out the time to backup/restore the reporting database, and also keep the HADR in sync by only using standard SQL logged statements.

It becomes obvious that the success of this solution depends on what “active” means. In our case, it meant all the records created during the last X months. All data inserted previously from X months was considered for archiving and should be visible only for auditing purposes, so we didn’t need to promptly migrate all. This solution seemed quite feasible and was the selected one for the $main$ table. We could agree on a reasonable value for X, and we felt comfortable with the estimated time to trickle-feed the data.

The final solution

In the end, the final solution was a combination of different strategies. For the biggest $main$ table, we chose the “Duplicate table and migrate active data”. For the $auxiliar$ tables, we went for the “Alter table command” as these tables were small enough to complete the operation in less than one hour (we got to this conclusion by testing the command on our sandbox DB with a backup from OLTP). Finally, for the $reporting$ table, we went for the “Admin move table command” as we didn’t require HADR for the reporting database.

So far, we discussed only the high-level details. Next, the following table presents and reasons for each step taken.

| Step | Reasoning |

|---|---|

| 1. Create new table | At this stage, we created the new duplicate table main_bigint with the ID definition to BIGINT. We also created the same indexes as per the original table to avoid indexing time during the switchover. We didn’t create any triggers at this moment to keep the data consistent and to prevent duplicated actions on the DB. The main_bigint was created way before switching over to guarantee we would have X months of “active” data |

| 2. Create ETL triggers | Just after creating the main_bigint table, we created the ETL triggers. These triggers aimed to duplicate all insert/update/delete commands made on the main table into the main_bigint table. Notice that records inserted before the creation of the ETL triggers were not automatically synchronized, this was intentional to prevent upsert commands that are quite expensive operations (we needed these triggers to be performant). Before releasing these triggers we ran performance tests to make sure that the general performance of the application wouldn’t degrade. The triggers approach was essential to know which records were synchronized or not, every time an insert was made on the main table we flagged that record as synchronized by the triggers. We used an old column of another aggregator table for that purpose. |

| 3. New application version deploy | By the time we deployed the new application version, it version had all java code adapted to handle long key values. The application also had a mechanism in place to prevent non-sync-flagged records from being accessed. At first, we kept this mechanism disabled with a feature flag and only enabled it after the switchover. It was required because not all records would be present after the switchover. |

| 4. Pre-fill data | When he decided on the switchover date, we were in a position to establish how many months of “active” records we wanted on the main_bigint table. At this point, we noticed that around 1K records were missing on main_bigint, and we wrote a simple store procedure to sync all these records. In this procedure we needed to use cursor stability to lock the records in the main table during the copy, we didn’t want to synchronize stale data. |

| 5. Foreign keys removal | At this stage we dropped all the Fks to main_bigint, this was required to enable the capability of switching the table’s names of main and main_bigint. Before dropping the FK’s we made extensive tests and validations to certify we would not create orphan records. We didn’t want to mess up with reports reading records not associated with any valid parents. |

| 6. Alter dependent tables | At this stage, during the night, we put the application down and killed all DB connections for one hour. Then we could safely run the alter table and reorg commands on the auxiliary tables. Because these tables were small we could convert them in less than one hour. |

| 7. Switch tables main and main_bigint | At this stage, we switched the table names. However, before doing that we first put the application down, killed all DB connections, and dropped all MQTs, views, procedures, and triggers. Then we switched the names, deleted the ETL triggers, and re-created all MQTs, views, procedures, and triggers. Finally, we ran some tests before starting up the application. The whole operation took less than 20 minutes. Notice that we still had the main_int table in case a rollback was needed. |

| 8. Move the old main table out of the OLTP DB | At this stage, we moved the old main_int table to a sandbox DB to free up space in the main OLTP DB and to reduce the reporting backup/restore process. |

| 9. Start back-fill | When the old table was moved out to the sandbox DB, we set up a federation connection between the main DB and the sandbox DB to start the backfilling process. For all records marked as unsynchronised, we back-fill the records to the new main table using stored procedures. Every time a record was backfilled we flagged it as sync’d so the locking mechanism wouldn’t block this record in auditing processes. |

| 10. Migrate reporting tables | Finally, we migrated the reporting affected tables using the admin move table command. As mentioned we used this command because we didn’t need logged operations for HADR. |

| 11. AB test | After switching all tables and backfilling the data we ran an AB test scenario to check if a controlled business transaction would flow with large keys across the company. We implemented the AB test by deviating the keys generation flow given specific parameters used in the transaction, so we could dynamically activate it. |

| 12. Switch to large keys | When we were comfortable with all tests, we switched the main table sequence generator to use large keys. We did that beforehand because we didn’t want to wait for the natural overflow of the keys, so we could anticipate any production error not predicted beforehand. Also if we needed to rollback for any reason to the last INT key value, we could do that with minimum data loss. |

Various details were omitted in the table above to prevent exposing the business domain. For example, the testing strategy for all implementation and deployment steps wasn’t presented because they were very specific to the business. Also, the way we flagged the synced records in the main table wasn’t detailed because it was dependent on the application domain. Therefore you’ll need to work out these details by yourself in your use case if you are facing such a similar problem.